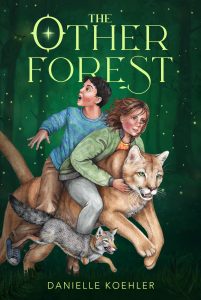

“I couldn’t even get past the cover. We are opposed to images of people touching wild animals… We have way too much fantasy surrounding the nature of wild animals and need to do a lot more to encourage respect than continue down the path that has brought most wild cats to the edge of extinction.”

I stared at my computer screen with my jaw hanging low. I had just emailed a well-known big cat rescue center in the U.S. a request to review my book The Other Forest, since my characters were based on real animals from a rescue center in southern Chile, and I thought they would appreciate the conservation theme at the heart of my story. I certainly did not expect a famous animal activist to respond. Not only did she respond, but she was adamantly opposed to my book, all because the cover shows two children riding through a forest on a puma’s back!

Swallowing my shock, I responded that I understood and respected her stance. I meant it wholeheartedly, though it did make me wonder. Are animal fantasy stories really doing more harm than good?

While researching this issue, I came upon the Big Cat Sanctuary Alliance, a group of 16 member sanctuaries dedicated to ending private ownership and commercial exploitation of wild cats in the United States. On their website, they state the following: “There is evidence to suggest that media representations of wild animals can negatively affect the public’s perception of the endangered status of those animals. A study by Ross et al. (2011) found that people who viewed a photograph of a chimpanzee shown in a human setting (e.g., an office) or with a human standing nearby were more likely to consider wild populations to be stable and healthy – when in fact chimpanzees are highly endangered. The presence of a human in the photo also increased the likelihood that the person would consider chimpanzees to be appealing as a pet.”

That makes perfect sense. There’s already an adorable child-like quality to chimpanzees. If you put one in a shirt and place him in an office, you make it even easier to imagine sharing a home with one. But what if the problem is all about the context? Perhaps the issue is isolated to media which takes chimpanzees out of their jungle environment and places them in human settings such as offices, or takes lions out of the savannah and shows them jumping through hoops in a circus. Of course they seem more domestic if they’re in domestic settings. But what if we flip the script? Does media depicting people sharing a space with wild animals in settings such as a forest create this same perception of wild animals as pets?

This question brought me back to an interesting research article that I read years ago when I first sat down to write my book. In it, the researchers studied the impact that Mapuche traditional folktales (called epews) had on locals’ feelings towards pumas and kodkods. To give an example of these traditional folktales, “Fütra Peñi” by Luis Levio Curilen tells the story of a group of Mapuches who were forced to take shelter in the mountains until their food ran out. Watching the people cry out in hunger, the pumas descended the mountain, hunting for food which they then brought back to save the people from starvation. From that day forth, the people called the puma their “great brother.”

The researchers found that in areas where these beautiful folktales remained prevalent and gave the animals a positive, spiritual symbolism (the puma as a guardian), conflict with humans was less common. The researchers conclude that conservation initiatives should take an interdisciplinary approach, including creating bio-cultural books containing narratives and illustrations of kodkods, pumas, and other threatened carnivores.

It’s not difficult to understand why creating books would be their first recommendation. Children develop their values, including feelings towards animals and the environment, at a young age, and these values are often resistant to change later on. Think about this: if children grow up seeing a panther, snake, or shark represented as the villain of every story they ever read, they’re bound to have negative feelings toward those animals. They may not grow up to become shark-hunters, but they will be less motivated to fight for their protection when the time comes.

This brings us back to the issue of “images of people touching wild animals.” The activist who had an issue with my cover claims that these images encourage people to pay to see and touch captive born cubs which has caused us to “continue down the path that brought most wild cats to the edge of extinction.” Because I no longer live in the United States, I did not consider this context at all. Owning and breeding wild animals is strictly forbidden in Chile, as are “pay to pet” zoos.

Unfortunately, the U.S. government has not yet made this illegal like Chile has. In December of 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives passed bill H.R. 1380, more commonly known as the Big Cat Public Safety Act, which bans the possession and exhibition of big cats. Unfortunately, the bill was never passed by the Senate, meaning that the bill has not yet become law. I would argue that the responsibility to protect these animals from captive breeding lies with our governments, not our children.

While I understand that this is a complex issue and these wildlife activists have an incredible passion for these animals and would do anything to protect them, I disagree that the solution lies in children abstaining from fantasy stories showing humans touching animals. Fantasy, when done correctly, can be a force for good. I personally was inspired by the Mapuche folktales focusing on positive human-animal relationships, and I believe that this type of fantasy storytelling, along with more traditional methods of teaching about wildlife, will create more passionate conservationists who will be better equipped at devising creative solutions that older generations have failed to see. And maybe, just maybe, they could even grow up to become animal-loving senators who will more effectively pass laws to protect our planet and the wildlife which inhabits it.

References

Ross SR, Vreeman VM, Lonsdorf EV (2011) Specific Image Characteristics Influence Attitudes about Chimpanzee Conservation and Use as Pets. PLOS ONE 6(7): e22050. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022050

Herrmann, T.M., Schüttler, E., Benavides, P. et al. Values, animal symbolism, and human-animal relationships associated to two threatened felids in Mapuche and Chilean local narratives. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 9, 41 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-41

I’m not sure. I own copy of of THE OTHER FOREST. I read it and enjoyed it, but perhaps more as a book about Chile than about cougars. What are some fantasy books about animals in English? The only one I can think of besides THE OTHER FOREST that I’ve read (as a child; I’m now 83) is WINNIE THE POOH. There are the CHRONICLES OF NARNIA, which I haven’t read. The stories and illustrations by Ernest Thompson Seton, which were about real animals, who almost always died tragic deaths, were the most influential. I would read them and cry and cry. Recently I have read some books for children and young adults which are readable and influential, but they aren’t fantasies.

Hi Helen! There are a lot of fantasy books about animals. Narnia is a good example of a classic, as well as Charlotte’s Web, The Golden Compass, and The Jungle Book. Some more modern examples would be The One and Only Ivan, The Total Eclipse of Nestor Lopez, The Hedgehog of Oz, and I want to say Pax because I loved it, but I’m not sure it classifies as fantasy. It does have one half of the book told from the Fox’s perspective.